Replacing Protobuf with Rust to go 5 times faster

Jan 22nd, 2026

Lev Kokotov

PgDog is a proxy for scaling PostgreSQL. Under the hood, we use libpg_query to parse and understand SQL queries. Since PgDog is written in Rust, we use its Rust bindings to interface with the core C library.

Those bindings use Protobuf (de)serialization to work uniformly across different programming languages, e.g., the popular Ruby pg_query gem.

Protobuf is fast, but not using Protobuf is faster. We forked pg_query.rs and replaced Protobuf with direct C-to-Rust (and back to C) bindings, using bindgen and Claude-generated wrappers. This resulted in a 5x improvement in parsing queries, and a 10x improvement in deparsing (Postgres AST to SQL string conversion).

Results

You can reproduce these by cloning our fork and running the benchmark tests:

| Function | Queries per second |

|---|---|

pg_query::parse (Protobuf) |

613 |

pg_query::parse_raw (Direct C to Rust) |

3357 (5.45x faster) |

pg_query::deparse (Protobuf) |

759 |

pg_query::deparse_raw (Direct Rust to C) |

7319 (9.64x faster) |

The process

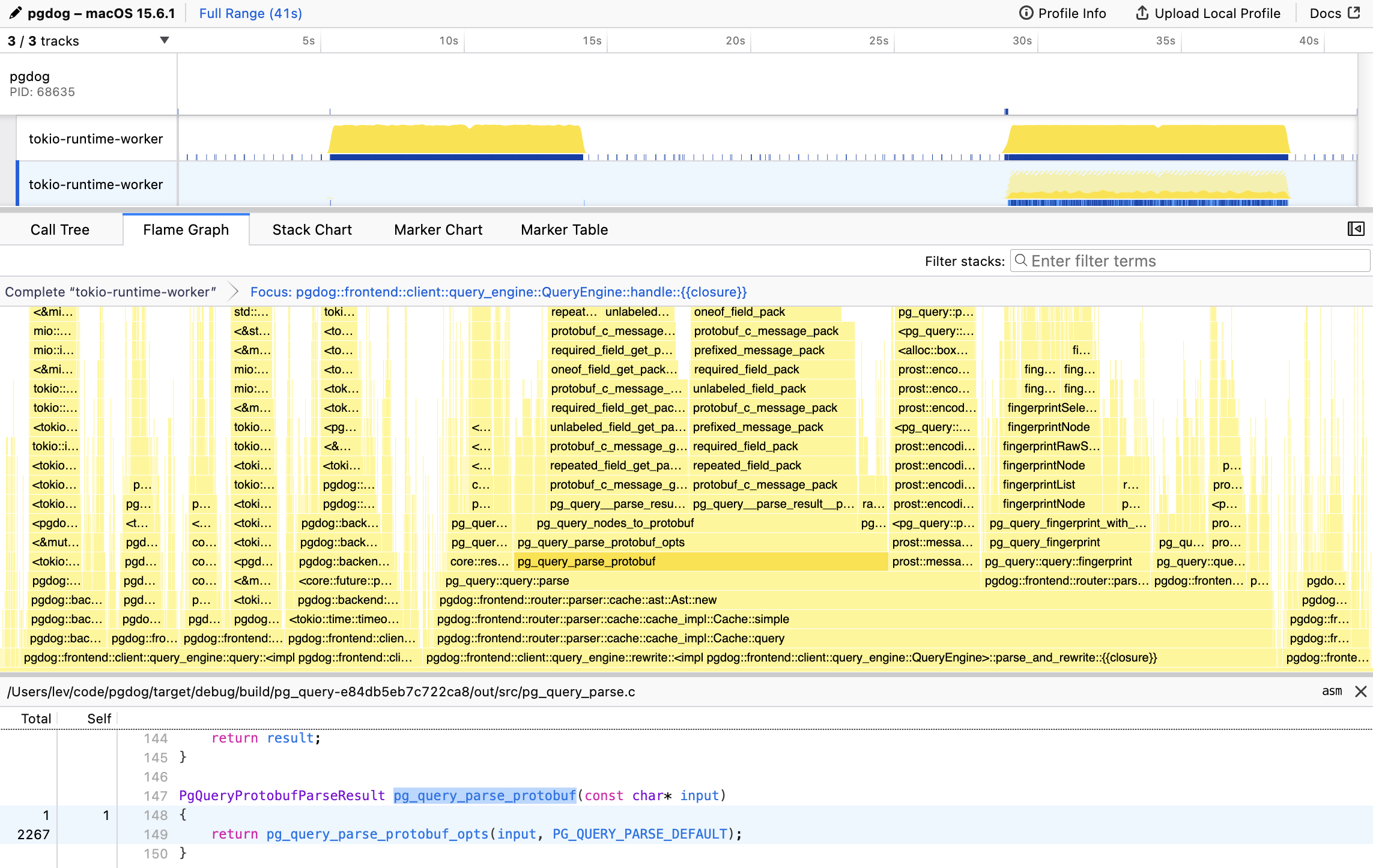

The first step is always profiling. We use samply, which integrates nicely with the Firefox profiler. Samply is a sampling profiler: it measures how much time code spends running CPU instructions in each function. It works by inspecting the application call stack thousands of times per second. The more time is spent inside a particular function (or span, as they are typically called), the slower that code is. This is how we discovered pg_query_parse_protobuf:

This is the entrypoint to the libpg_query C library, used by all pg_query bindings. The function that wraps the actual Postgres parser, pg_query_raw_parse, barely registered on the flame graph. Parsing queries isn’t free, but the Postgres parser itself is very quick and has been optimized for a long time. With the hot spot identified, our first instinct was to do nothing and just add a cache.

Caching mostly works

Caching is a trade-off between memory and CPU utilization, and memory is relatively cheap (latest DRAM crunch notwithstanding). The cache is mutex-protected, uses the LRU algorithm and is backed by a hashmap1. The query text is the key and the Abstract Syntax Tree is the value, which expects most apps to use prepared statements. The query text contains placeholders instead of actual values and is therefore reusable, for example:

SELECT * FROM users WHERE id = $1;

While the id parameter can change between invocations, the prepared statement does not, so we could cache its static AST in memory.

This works pretty well, but eventually we ran into a couple of issues:

- Some ORMs can have bugs that generate thousands of unique statements, e.g.,

value IN ($1, $2, $3)instead ofvalue = ANY($1), which causes a lot of cache misses - Applications use old PostgreSQL client drivers which don’t support prepared statements, e.g., Python’s

psycopg2package

The clock on Protobuf was ticking and we needed to act. So, like a lot of engineers these days, we asked an LLM to just do it for us.

Tight constraints

I’m going to preface this section by saying that the vast majority of PgDog’s source code is written by a human. AI is not in a position to one-shot a connection pooler, load balancer and database sharder. However, when scoped to a very specific, well-defined and most importantly machine-verifiable task, it can work really well.

The prompt we started with was pretty straightforward:

libpg_query is a library that wraps the PostgreSQL parser in an API. pg_query.rs is a Rust wrapper around libpg_query which uses Protobuf for (de)serialization. Replace Protobuf with bindgen-generated Rust structs that map directly to the Postgres AST.

And after two days of back and forth between us and the machine, it worked. We ended up with 6,000 lines of recursive Rust that manually mapped C types and structs to Rust structs, and vice versa. We made the switch for parse, deparse (used in our new query rewrite engine, which we’ll talk about in another post), fingerprint and scan. These four methods are heavily used in PgDog to make sharding work, and we immediately saw a 25% improvement in pgbench benchmarks2.

Just to be clear: we had a lot of things going for us already that made this possible. First, pg_query has a Protobuf spec for protoc (and Prost, the Protobuf Rust implementation) to generate bindings, so Claude was able to get a comprehensive list of structs it needed to extract from C, along with the expected data types.

Second, pg_query.rs was already using bindgen, so we had to just copy/paste some invocations around to get the AST structs included in bindgen’s output.

And last, and definitely not least, pg_query.rs already had a working parse and deparse implementation, so we could test our AI-generated code against its output. This was entirely automated and verifiable: for each test case that used parse, we included a call to parse_raw, compared their results and if they differed by even one byte, Claude Code had to go back and try again.

The implementation

The translation code between Rust and C uses unsafe Rust functions that wrap Rust structs to C structs. The C structs are then passed to the Postgres/libpg_query C API which does the actual work of building the AST.

The result is converted back to Rust using a recursive algorithm: each node in the AST has its own converter function which accepts an unsafe C pointer and returns a safe Rust struct. Much like the name suggests, the AST is a tree, which is stored in an array:

unsafe fn convert_list_to_raw_stmts(

list: *mut bindings_raw::List

) -> Vec<protobuf::RawStmt> {

// C-to-Rust conversion.

}

For each node in the list, the implementation calls convert_node, which then handles each one of the 100s of tokens available in the SQL grammar:

unsafe fn convert_node(

node_ptr: *mut bindings_raw::Node

) -> Option<protobuf::Node> {

// This is basically C in Rust, so we better check for nulls!

if node_ptr.is_null() {

return None;

}

match (*node_ptr).type_ {

// SELECT statement root node.

bindings_raw::NodeTag_T_SelectStmt => {

let stmt = node_ptr as *mut bindings_raw::SelectStmt;

Some(protobuf::node::Node::SelectStmt(Box::new(convert_select_stmt(&*stmt))))

}

// INSERT statement root node.

bindings_raw::NodeTag_T_InsertStmt => {

let stmt = node_ptr as *mut bindings_raw::InsertStmt;

Some(protobuf::node::Node::InsertStmt(Box::new(convert_insert_stmt(&*stmt))))

}

// ... 100s more nodes.

}

}

For nodes that contain other nodes, we recurse on convert_node again until the algorithm reaches the leaves (nodes with no children) and terminates. For nodes that contain scalars, like a number (e.g., 5) or text (e.g., 'hello world'), the data type is copied into a Rust analog, e.g., i32 or String.

The end result is protobuf::ParseResult, a Rust struct generated by Prost from the pg_query API Protobuf specification, but populated by native Rust code instead of Prost’s deserializer. Reusing existing structs reduces the chance of errors considerably: we can compare parse and parse_raw outputs, using the derived PartialEq trait, and ensure that both are identical, in testing.

While recursive algorithms have a questionable reputation in the industry because bad ones can cause stack overflows, they are very fast. Recursion requires no additional memory allocation because all of its working space, the stack, is created on program startup. It also has excellent CPU cache locality because the instructions for the next invocation of the same function are already in the CPU L1/L2/L3 cache. Finally and arguably more importantly, they are just easier to read and understand than iterative implementations, which helps us, the humans, with debugging.

Just for good measure, we tried generating an iterative algorithm, but it ended up being slower than Prost. The main cause (we think) was unnecessary memory allocations, hashmap lookups of previously converted nodes, and too much overhead from walking the tree several times. Meanwhile, recursion processes each AST node exactly once and uses the stack pointer to track its position in the tree. If you have any ideas on how to make an iterative algorithm work better, let us know!

Closing thoughts

Reducing the overhead from using the Postgres parser in PgDog makes a huge difference for us. As a network proxy, our budget for latency, memory utilization, and CPU cycles is low. After all, we aren’t a real database…yet! This change improves performance from two angles: we use less CPU and we do less work, so PgDog is faster and cheaper to run.

If stuff like this is interesting to you, reach out. We are looking for a Founding Software Engineer to help us grow and build the next iteration of horizontal scaling for PostgreSQL.